Abstract

Background

Vacuoles, E 1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory somatic (VEXAS) syndrome is a recently described systemic disease caused by somatic mutations in UBA1 gene. Patients may present for hematology consultation with blood count abnormalities; most commonly with macrocytic anemia but also leukopenia (lymphopenia/neutropenia), thrombocytopenia, or monocytopenia. Here we report a series of patients who presented with eosinophilia and skin rash as one of the initial manifestations of VEXAS.

Methods

Patients with VEXAS diagnosis who were seen at National Institutes of Health (NIH) between 2013 and 2022 were included. Records from outside and NIH evaluations were reviewed to collect demographics, disease phenotype, blood counts, marrow and aspirate findings, treatment, and outcomes.

Results

Thirty subjects with VEXAS were included and four (13%) patients were identified to have eosinophilia in peripheral blood on presentation. The median age at onset of inflammatory symptoms in VEXAS patients with eosinophilia was 68 years (range 57 - 71), which was similar to that in the VEXAS cohort as a whole (median 61 years). The presence of eosinophilia was not associated with UBA1 genotype, atypical inflammatory or hematologic manifestations.

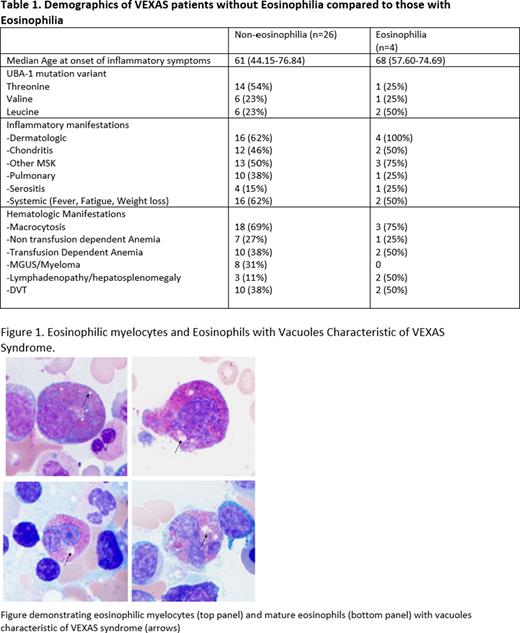

All four subjects with eosinophilia presented with concurrent skin rash. Median absolute eosinophil count (AEC) at earliest complete blood count (CBC) was 0.63x103 µ/L (0.5-2.19), with median neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts of 2.65 x103 µ/L (2-3.85), 0.885 x103 µ/L (0.3-1.1) and 0.35 x103 µ/L (0.26-0.46), respectively. All patients were negative for ANCA antibodies. Bone marrow eosinophilia decreased over time in all 4 patients from a median percentage of bone marrow eosinophils at 1st bone marrow biopsy (BMBx) of 10.5% (3-20%) to 3.4% (1-4) at 1st NIH BMBx later in the disease course. Vacuoles characteristic of VEXAS were visualized within eosinophilic myelocytes and mature eosinophils (Figure 1). Further analysis of eosinophils was performed on the NIH BMBx in three patients. The expression of CD69, a marker of eosinophil activation, was increased with median expression of 29.2% in the three patients versus 16.79% in healthy donors, suggesting that eosinophils may be more activated in the setting of VEXAS. Flow cytometry on mast cells did not reveal aberrant CD2/CD25 expression. Molecular testing was negative for molecular abnormalities involving PDGFRA/B, BCR::ABL and KIT. A UBA1- mutation was detected in a purified population of eosinophils (Ficoll-Hypaque separation followed by immunomagnetic negative isolation utilizing autoMACs®) with a VAF of 9%.

In the four patients with VEXAS and eosinophilia, the characteristics of the rash varied over the disease course. The initial skin biopsies of 3 patients demonstrated perivascular dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprised predominantly of eosinophils and attributed to a hypersensitivity reaction. Two of these patients had later biopsies demonstrating neutrophilic dermatosis consistent with Sweet Syndrome. The remaining patient presented with urticaria and subsequently had a biopsy demonstrating a diffuse inflammatory infiltrate consisting of eosinophils involving dermis, subcutis and vessels.

All patients had a sustained reduction in eosinophilia with corticosteroid treatment and a normal AEC at last follow up.

Conclusion

Blood eosinophilia and pruritic eosinophil-rich urticaria-like skin eruptions may be the initial presentation of VEXAS syndrome in some patients. Therefore, in addition to evaluation for secondary causes of eosinophilia and primary hyper-eosinophilic syndrome, UBA1 mutation testing should be considered, particularly in older men with other blood count abnormalities. Eosinophils can carry the UBA1 mutation and appear more activated in VEXAS.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal